By Ellen Caswell, Policy Advisor, Future of Money.footnote [1]

Cash plays a key role in society – it is used both as a medium of exchange to connect buyers and sellers, and as a store of value. As the sole issuer of banknotes in England and Wales, we are responsible for ensuring that people have genuine, high-quality and durable banknotes that they can use with confidence. This includes deciding how many banknotes to print to ensure we meet demand at all times.

For a number of years, people in the UK have been using less and less cash as part of their everyday spending. But the total value of notes in circulation (NIC) has actually increased as people choose to hold more cash. These trends have persisted for a number of years and have been amplified by the Covid pandemic.

In November 2020, we published a Quarterly Bulletin article that explored cash trends in the early days of the pandemic. As we enter a ‘post-lockdown’ world, this article takes a look at how cash use and cash demand have evolved, and the possible drivers of these trends – both from a transactional and store of value perspective.

We find that, while Covid has had a lasting impact, with some permanent shifts in payment habits towards digital payment methods, cash use has proved resilient, perhaps surprisingly so. There has been a partial recovery in the transactional use of cash, and the value of NIC remains elevated two years on from the start of the pandemic, reflecting people holding more cash as a store of value. Cash therefore continues to be an important form of money for many – one in five peoplefootnote [2] consider it to be their preferred payment method and 1.1 million people Opens in a new window rely on it for their everyday spending. Even for those who may not use it day-to-day, cash remains an important back-up option.

The future trajectory of cash remains uncertain. Our work to understand the ‘new normal’ is therefore ongoing, and we continue to monitor trends in both cash use and cash demand (ie NIC).

Prior to the pandemic, the UK had experienced a marked decline in the use of cash to pay for goods and services. Only 23% of payments in 2019 Opens in a new window were made in cash, down from around 60% a decade ago. In 2020 when the pandemic was in its early stages, this figure dropped by 35% compared to 2019, with cash accounting for 17% Opens in a new window of all payments. Since 2017 cash use had been declining by around 15% each year Opens in a new window, so 2020 represented an acceleration of this decline.

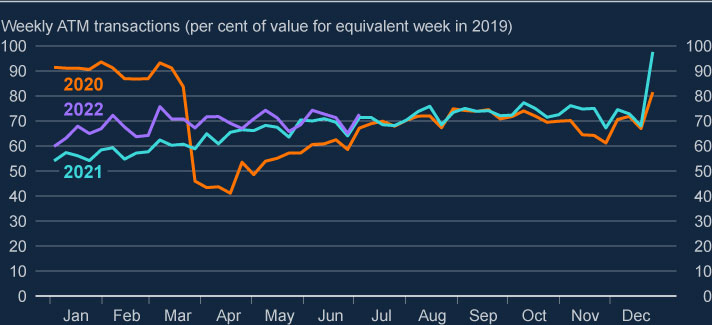

There has since been a sustained, if partial, recovery in cash use, and more recently, signs of stabilisation in cash use trends. In 2021, there was a reduction in the rate of decline in cash use, with cash accounting for 15% of all payments Opens in a new window in the UK. Moreover, an estimated 73% of consumers Opens in a new window said they used cash in January 2022, a notable increase from only around half of consumers in mid-2020. The recovery in cash use can also be seen in ATM withdrawals (Chart 1).footnote [3] These fell sharply at the start of the pandemic: overall withdrawal values decreased by 50%, with even larger falls in city centres and transport hubs. Since then, consumers have been withdrawing more cash, and overall cash use has been largely stable since around mid-2020, hovering at about 30% below pre-pandemic levels. This suggests that, at least in the near term, cash use has stabilised.

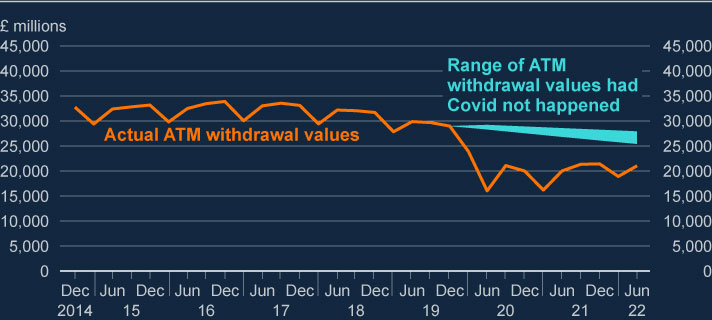

Given cash use was on a declining trend prior to the pandemic, it is worth considering the additional impact of the pandemic on cash use. By extrapolating the declining trend in ATM withdrawal values in the years before the pandemic (Chart 2), we find that, in 2022 Q2, ATM use was around a fifth down on where it might otherwise have been. This suggests that Covid has accelerated the pre-pandemic trends seen in cash use, and may have brought forward cash decline by over five years, reflecting a change in people’s payment preferences.

What remains highly uncertain is where cash use will head next. On the one hand, Covid appears to have brought forward, and accelerated the rate of change in payment preferences. On the other, if those who were most likely to change their behaviour already have, then the pace of change may actually slow. UK Finance expect this to happen Opens in a new window, and predict that by 2031, 6% of all payments will be made in cash. Understanding what influenced demand during the pandemic, and subsequent recovery, might offer some clues about cash’s future trajectory.

In our previous Quarterly Bulletin article we identified four factors that were impacting the public’s use of cash during the pandemic. These included: overall levels of consumer spending; online shopping; attitudes to cash versus alternative payment methods; and cash acceptance. Below we explore how these have changed over the past 18 months, with Table A providing a summary of the findings.

| Driver | Explanation | Change since end-2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Consumption | Increase in consumers’ opportunities to spend as lockdown restrictions eased. | Consumption, including cash transactions (as proxied by cash centre inflows), has increased.But cash transactions in 2022 remain below pre-pandemic levels. |

| Online shopping | Partial reversion in the way people shop towards in-person payment methods (as opposed to online) due to less concerns over virus transmission. | Online share of retail spending – which does not allow for cash use – has decreased since its lockdown peak, though remains above pre-pandemic trends. |

| Consumer attitudes to cash versus other payment methods | Less concerns about the risk of Covid transmission via banknotes. | Survey results suggest a decrease in people’s concerns about handling cash for hygiene reasons. |

| Retailer action regarding cash acceptance | Less restrictions on the way people pay in shops, as retailers no longer encourage cashless payment methods. | Market intelligence suggests the majority of retailers are accepting cash and no longer actively encouraging contactless payments.Survey results suggest a decrease in people encountering a shop that does not accept cash. |

The recovery in overall household spending Opens in a new window, which as at 2021 Q4 had almost returned to pre-pandemic levels, has supported increased cash use.footnote [4] This reflects the reopening of the retail sector – following temporary closures amounting to 8 months for shops and ten months for indoor hospitality – as well as the lifting of all social distancing restrictions.footnote [5] It also likely reflects the fact that for many households, incomes were supported by the availability of government schemes such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme and the Self-Income Support Scheme.

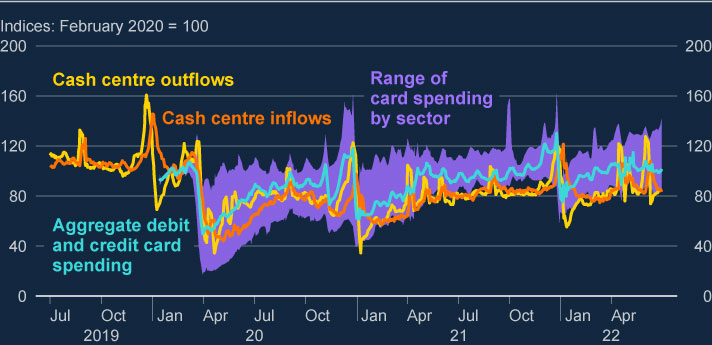

Although cash transactions have increased since the start of the pandemic, they remain below their pre-pandemic levels. And they have not recovered to the same extent as consumer debit and credit card payments (Chart 3). This suggests there was also a shift in people’s payment preferences during the Covid pandemic.

One factor that is likely to have driven this shift in people’s payment preferences during the pandemic is the concern over virus transmission. In particular, it is likely to have changed both the way people shopped (online or in store) and the types of payment methods they used in store (cash or card).

The pandemic saw an increase in online shopping Opens in a new window, with the online share of UK retail spending peaking at 36% in February 2021, compared with 20% a year earlier (Chart 4). At least part of this can be attributed to government restrictions put in place as a result of Covid, such as the closure of high street shops, which limited the opportunities available for consumers to spend cash in-store. The online share of retail sales has subsequently fallen back, and in June 2022, accounted for 25% of UK retail spending, which may have increased opportunities to pay with cash. That being said, online spending remains popular, with its share of retail sales remaining above pre-pandemic trends.

As well as prompting a shift towards online shopping, Covid also affected the types of payment methods that people used in-store. This is due to a combination of consumers’ attitudes to cash versus other payment methods, as well as retailers’ actions on cash acceptance.

In terms of attitudes to cash, people have become more willing to use cash since the height of the pandemic. Our survey in October 2021 found that 27% of respondents were using less cash because they were worried about handling cash for hygiene reasons. This is a decrease from previous Bank surveys in 2020 and 2021, which saw this figure peak at 39%. Attitudes have perhaps evolved as the general concern over virus transmission has reduced along with increased understanding that cash use does not pose a greater risk than any other payment type.footnote [7] That being said, 56% of respondents in our survey in October 2021 were using less cash since the start of the pandemic because they preferred using cashless payment methods. This suggests some permanent shifts in payment habits towards digital methods.

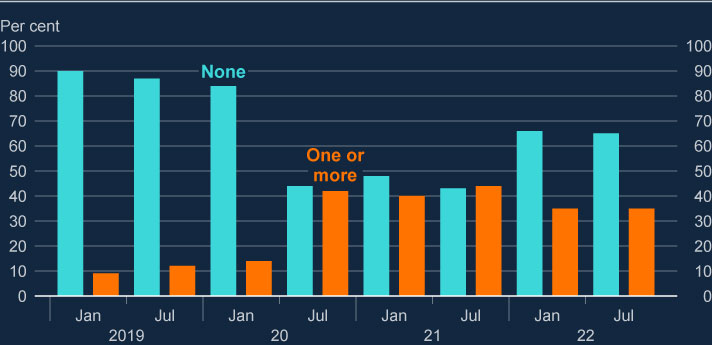

In terms of cash acceptance, we interviewed a number of large retailers in 2022 H1 to discuss the payment trends they were seeing, and their payment strategies going forward. Our interviews indicate that the vast majority of large retailers are accepting cash and no longer actively encouraging contactless payments. Retailers told us that they are ambivalent to the payment methods that consumers choose to use. This represents a shift from early on in the pandemic when – in line with UK Government advice – many retailers, including the large supermarkets, encouraged consumers to use contactless payments, although most still accepted cash. This is reflected in the data: our latest survey suggests that the number of people encountering a store that did not accept cash has fallen: from 44% in July 2021 down to 35% in July 2022 (Chart 5). Furthermore, 98% of small business owners Opens in a new window have said that if a customer needed to pay in cash they would not refuse them.

Looking ahead, research conducted by the Financial Conduct Authority Opens in a new window during the pandemic found that 80% of small and medium-sized enterprises think they are very likely to accept cash over the next five years. This suggests that retailers consider cash to be a relevant payment offering and one that their customers still want to use.

It is clear that the pandemic has had an impact on payment habits, with some shifting permanently towards digital payment methods. It is unlikely that cash use will recover much further from its current level, as reflected by the recent stabilisation in transactional cash use data. We are still in the early days of ‘post-lockdown’ however – we may be able to learn more about the future trajectory of cash use by considering which groups in society have a strong preference to use cash.

Cash remains an important payment method in the UK, and a critical means of payment for many people. This is borne out by research on consumer attitudes to cash. Our survey in July 2022 found that around one in five respondents consider cash to be their preferred payment method, and so use it day to day. This figure has not varied significantly over the course of the pandemic – or compared to pre-pandemic – suggesting that a significant proportion of those reliant on cash did not make the switch to contactless or digital payment methods.

Cash remains a valued form of money for the elderly and those on lower incomes, with many using it to budget and manage their household finances. In July 2022, cash as first preference payment method was most popular among those aged 65+ at 27%, up from 20% in July 2021 (but still below pre-pandemic figures of 38% in January 2020).footnote [8] It continues to be most prevalent among those in lower socio-economic groups C2, D and E (28% in July 2022). It is important to recognise, however, that preference for cash depends on a range of factors – not just age or social grade. These include education, wealth and health. For example, a 2020 survey by the Financial Conduct Authority Opens in a new window found that 46% of the digitally excluded, 31% of those with no educational qualifications, and 26% of those in poor health rely on cash to a ‘great or very great extent’. Furthermore, some people with physical and cognitive disabilities Opens in a new window find other payment methods difficult to use (due to not being able to remember a PIN for example).

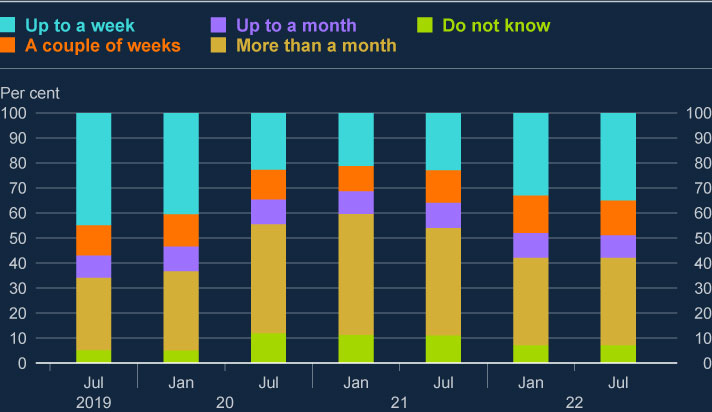

Even those who do not use cash on a day-to-day basis find it a valuable form of money. Our survey found that just 35% of respondents in July 2022 thought they could go more than a month without cash (Chart 6). This is a decrease from January 2021 where the figure was higher at 48%, and a return to pre-pandemic figures.

Cash is also recognised as an important backup option. In our survey in March 2022, 85% of respondents said that they think that cash should be there for backup, for example in case technology fails or if a card is not accepted. Cash was also considered by respondents as the payment method that is ‘the most safe, convenient and trustworthy’. Seventy-eight per cent of respondents think that it is important that there is a physical form of money and 88% agree that ‘banknotes should be there for people who need, or want, to use them’.

Taken together, this suggests that Covid has had a sizable impact on cash demand, but for a sizable proportion of the population cash remains vital and so is likely to be a critical part of the UK payments landscape to come. The Bank and other UK authorities remain committed to supporting cash as a viable means of payment and are taking action to protect it. For more detail, see Box A.

For cash to remain a viable payment method, the public needs to be able to access it. The cash infrastructure that helps ensure effective distribution of cash around the UK was built for a time of much higher cash usage. The Bank, other UK authorities and the cash industry have therefore taken steps to ensure that this cash infrastructure remains fit for purpose, both on the retail side – cash withdrawal and deposit by households and businesses – and the wholesale side – the sorting, authentication, storage and distribution of cash.

In July 2022, new legislation was introduced Opens in a new window to UK Parliament as part of the Financial Services and Markets (FS&M) Bill to protect cash by ensuring its continued retail access. In particular, the legislation aims to: ensure that people do not have to travel beyond a reasonable distance to withdraw or deposit money;footnote [9] designate the firms that will be responsible for meeting these geographic requirements; and ensure that the Financial Conduct Authority has appropriate regulatory oversight of cash service provision. The UK Government consulted on these Opens in a new window legislative proposals in July 2021.

The cash industry is also taking additional action in the retail space, with banks, building societies and the Post Office working together to deploy shared solutions in communities that require access to cash.

The Bank’s primary responsibilities in the cash system relate to the supply and wholesale distribution of banknotes. The FS&M Bill introduced to Parliament in July 2022 also contained legislation Opens in a new window to provide the Bank with the powers it needs to keep the wholesale cash infrastructure effective, sustainable and resilient into the future. These powers were summarised in a policy statement Opens in a new window published by the UK Government in April 2022.

The powers will help underpin industry-wide commitments made by industry stakeholdersfootnote [10] to ensure the continued effectiveness, resilience and sustainability of wholesale cash infrastructure. These industry-wide commitments were published by the Wholesale Distribution Steering Group in December 2021. And through 2022 Q1, firms outlined to the Bank their individual, measurable commitments to which they are willing to be held to account, and against which the Bank has already started monitoring.

While transactional cash use fell, the value of Bank of England NIC actually increased during the pandemic (Chart 7). In fact, the value of NIC increased by £12.3 billion between end-March 2020 and end-June 2022. This represents a growth rate of 17%.

Since the Government’s removal of all Covid-related restrictions in August 2021, NIC has continued to grow. But it has done so at a slower rate. June 2022 year-on-year growth was close to zero (due to much stronger growth at the same time the year before). This suggests that, similar to trends in transactional cash use, Covid has had an impact on cash demand, with signs of stabilisation in recent months.

The continued rise in the value of NIC may, at first glance, appear at odds with falling transactional cash use. However, what this trend suggests is that cash is increasingly being used as a store of value, which is a fundamental role of money.

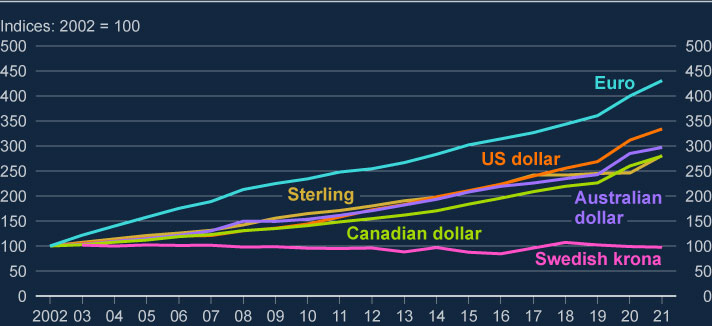

This trend is not new, and is a similar one to that seen in other countries (Chart 8). It is the reason for the 50% increase in the value of NIC in the UK between 2012 and 2021, despite falling transactional cash use over the same period. It is also consistent with the role that cash has played throughout history as a safe asset that people turn to in times of economic and social uncertainty, and when interest rates are low.

In our November 2020 Quarterly Bulletin article, we set out some possible explanations for the changes in NIC at the start of Covid. The primary drivers for the increase in cash demand that we identified were: people choosing to hold more cash as a store of value for contingency purposes (particularly in the early days of the pandemic); and cash taking longer to be deposited as Covid restrictions eased in mid-2020. This was evidenced by the weaker inflows of banknotes to Notes Circulation Scheme cash centres between April and August 2020.

There are several reasons why NIC has remained elevated, even two years on from the start of the pandemic when all government restrictions have been lifted and the UK economy is fully open.

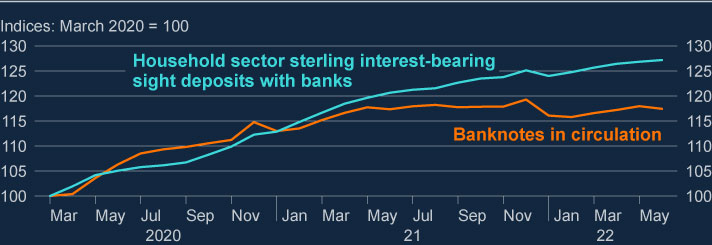

First, the three lockdowns that took place in the UK in 2020 and 2021 likely meant a build-up of cash due to people having fewer opportunities to spend it. This build-up of cash during the pandemic is somewhat similar to trends seen in other forms of money, such as deposits (Chart 9).

Although interest rates have started to rise in the UK, relatively low levels of interest rates over the past two years have also likely provided little incentive for people and small businesses to deposit the cash they have built up over the pandemic. In fact, historically, strong periods of banknote growth – due to greater economic or financial uncertainty or large exchange rate movements for example – have not seen a reversal in growth even when the shock itself dissipates. The same appears to be true here.

Economic uncertainty and rises in the cost of living over the past year may have also incentivised people to hold more cash over the past two years. We know from previous Bank surveys that the tangible nature of cash helps some people to budget and manage their household finances. A survey in May 2022 Opens in a new window by the consumer group, Which?, found that one in five respondents who do not regularly use cash expect to start using it if the cost of living continues to increase.

While travel restrictions have eased in many places, in some instances, travel restrictions (such as the requirement for pre-departure ‘fit to fly’ tests) remain in place. 2022 also saw travel disruptions, often due to staff shortages in the travel industry, which may be discouraging people from taking holidays overseas. Restrictions on international travel could be disrupting cross-border cash movements. In particular, it could be disrupting cash spending from tourism, suggesting that overseas demand for banknotes, at least in the earlier days of the pandemic, would be mostly to hold in reserve.

The future path of banknote demand remains uncertain, and will depend both on changes in cash’s store of value role as well as cash’s use for transactions. We have already seen a slowing in the growth rate of NIC this year. This growth may continue to slow, and perhaps NIC may even fall back from its current elevated level if the banknotes held in reserve over the past two years are spent and deposited.

In order to better understand the trend towards holding banknotes as a store of value domestically, we commissioned, oversaw and analysed the results of two surveys: on UK households’ use of banknotes as a store of value; and on self-employed individual’s banknote holdings and usage. We also conducted an international survey to assess the prevalence of Bank of England banknotes held overseas, see Box C.

Together these surveys enhanced our understanding of the drivers of the store of value trend that we have seen in the UK. This in turn has been useful in helping to improve our internal modelling and forecasting of the demand for banknotes, and can even help inform decisions on how many banknotes we should print.

In March 2021, we ran a household survey to gain further insights into people’s motivations for holding cash as a store of value and how these have changed over the past few years. Five thousand adults in England and Wales were surveyed using a combination of online and telephone interviews to ensure that we captured those who are not digitally connected (and who might well be higher cash users).

Our survey found that 60% of adults in England and Wales held cash in reserve. This chimes with research by UK Finance Opens in a new window conducted in June 2021, which found a similar proportion of people (59%) were holding cash at home. In our survey, the median amount of cash held was £167. About a third of respondents held less than £100, but a small group of people held large values.

Based on our analysis of the survey data, we estimate that around £10 billion to £30 billion of Bank of England banknotes are held in reserve by households domestically, and we have a high degree of confidence that at least £10 billion is held by households. See Box B for key caveats and assumptions made. Households holding cash in reserve is therefore likely to be a key driver of cash demand.

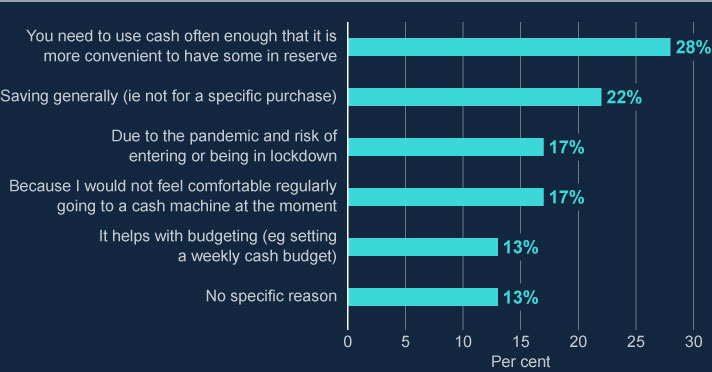

There are many reasons why people hold cash in reserve. But our survey suggests that the pandemic did cause a cohort of people (17%) to increase their holdings of cash (Chart 10). For those who said that they now hold cash in reserve even though they did not in the past (16%), the two main reasons given were because they were worried about an emergency (32%) or wanted to feel more in control of their money (22%).

Whether people hold cash in reserve or not does not vary significantly with age group. However, younger people are more likely to acquire cash as a gift from family and friends, whereas older people are more likely to acquire it from a bank branch or ATM. This suggests that older people are more actively seeking to hold cash in reserve.

Similar to the household survey, we also ran a survey in March 2021 to determine how much cash is held in reserve by self-employed individuals in England and Wales. This is because the self-employed are likely to be heavier-than-average cash users, and may hold more cash to run their businesses.

The survey comprised of 2,000 self-employed individuals using a combination of online and telephone interviews, designed to be representative of the adult population in England and Wales. Respondents who considered themselves to be freelancers, sole traders or self-employed were all classified as ‘self-employed’ for the purpose of our analysis.

Our survey found that in March 2021, 37% of the self-employed in England and Wales held cash in reserve. This translates to approximately 1.6 million self-employed people. Holding cash is more common among those with employees (64% among those with three to five employees) than those with none (49%). Interestingly, there is little relationship with turnover, length of time of self-employment, or most demographic indicators.

The median amount of cash held by the self-employed was £188, somewhat higher than for households. As expected, those businesses that take more payments in cash hold larger amounts of cash in reserve: 26% of those who take more than half of their payments in cash said that they hold more than £1,000.

Overall we estimate that £1.2 billion to £1.5 billion of Bank of England banknotes are held in reserve by the self-employed in England and Wales. Similar to the household survey, we made a number of assumptions to scale up our survey results to produce an estimate for the population as a whole. This included: weighting our sample data to mirror the demographic characteristics of the true population; removing and reweighting extreme values; and deciding whether and at what point to cap the distribution (winsorised mean).

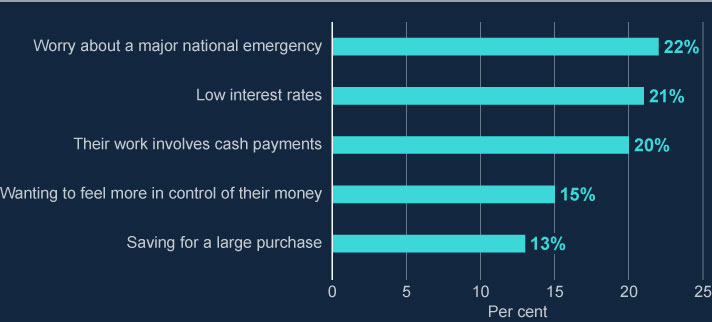

Our survey suggests that 16% of the self-employed who held cash in reserve three years ago, hold more now. And 35% hold less cash in reserve now compared to three years ago. There are several reasons why self-employed people now hold cash even though they did not three years ago (Chart 11).

We took a survey-based approach to estimate the total value of Bank of England banknotes held in reserve by households in England and Wales.

As these notes are not being used for transactions, they are not circulating frequently through the economy and therefore would not be processed regularly at cash centres as part of banknote authentication and fitness requirements.

There are a number of challenges of any survey-based approach. The first is that the demographic profile of the sample will rarely exactly mirror the demographic profile of the true population. To reduce this sampling bias, we weighted our sample data, using a method called raking, to mirror the demographic characteristics of the true population.

Another challenge is ensuring open and honest responses. Personal finances are a sensitive and private topic. And banknotes represent a physical security risk to those who hold them. Survey respondents may therefore be unwilling to provide data on their banknote storage habits, underreport the data or provide an extreme response – all of which skew the survey findings.

We aimed to address this response bias in a number of ways. We offered respondents a choice of how to share information on the value of cash held in reserve ie either as an open numerical response or selecting from closed range options. Furthermore, in analysing the data, we examined extreme values to assess whether they might be genuine or dishonest. We considered a range of approaches to adjust for extreme values we suspected might not be genuine. Reflecting the inherent uncertainty in these adjustments, we chose to present our estimate of banknotes held domestically as a range rather than as a point estimate. The width of this range (£10 billion to £30 billion) highlights the uncertainty of survey-based methodologies, especially when differentiating between noise (measurement error) and signal (relatively rare households with very high banknote holdings) at the tail of our sample distribution.

That being said, we are highly confident that at least £10 billion of Bank of England banknotes are held in reserve by households domestically in England and Wales.

A significant, but difficult to measure, source of demand for Bank of England banknotes is from non-residents. For example, we have observed increased demand for £50 (the highest denomination) banknotes when sterling depreciates.

Non-residents may choose to hold Bank of England notes as hard currency – as a store of value. They may also hold banknotes in preparation for a holiday in, or a relocation to, the UK. The inherent anonymity of banknotes, however, means that it is hard to estimate the value of UK banknotes held as a store of value overseas. Similarly, the foreign exchange market is highly fragmented and so it is hard to estimate the value of UK banknotes held within it, or by tourists.

Given these challenges, we ran some exploratory analysis in 2021 to further our understanding of the overseas demand for Bank of England banknotes across 11 countries.

The survey provided us with a number of insights. On average, 23% of respondents across all countries surveyed reported holding Bank of England banknotes. This result was higher than we anticipated, but plausible when compared against other currencies: 36% and 35% of respondents stated that they have US dollar banknotes and euro banknotes in their possession respectively. On average, those holding sterling banknotes hold £59. However, this varies significantly across countries.

As expected, tourism-related reasons are the most common for those holding Bank of England banknotes across all countries surveyed (63%). Only 16% of those holding Bank of England banknotes are doing so for store of value purposes. And 31% of respondents holding Bank of England banknotes received them as a gift.

These results gave us one of the first insights into the extent of overseas demand for Bank of England banknotes. Because this was an original piece of analysis, there are few other studies to compare the results to. But the results suggest that overseas holdings make up a significant portion of demand for our banknotes.

Over the past decade, the fall in transactional cash use in the UK has been accompanied by a rise in the value of notes in circulation. Covid intensified this trend.

As Covid restrictions have lifted, we have seen a partial recovery in cash use, and more recently, a stabilisation in cash use trends. The value of notes in circulation remains elevated even two years on from the pandemic, as people are holding more cash as a store of value.

Looking ahead, it seems unlikely that cash use will recover much further from its current level. This is likely to be the result of a permanent shift in payment habits towards digital payment methods as a result of the pandemic. However, there remains a sizable share of the population who value cash and for whom cash remains their preferred means of payment. Where cash trends go next – both in terms of speed and extent – will therefore be highly influenced by the payment preferences and behaviours of this group going forward.

Our work to understand these trends in cash demand and the drivers for change is ongoing. We conducted surveys in 2021 to gain further insights into the store of value role of banknotes. This included estimating the value of NIC that are held in reserve by households and the self-employed domestically. We will build on this analysis by estimating the value of banknotes held in the transactional cycle. We will also continue to engage with Note Circulation Scheme members and ATM operators to get an up-to-date view on customer demand for banknotes. We will continue to hold interviews with a range of large retailers to learn more about their cash holdings, the cash trends they are seeing and their attitudes to cash acceptance. This monitoring will contribute to our assessment of the future path of NIC and transactional demand. This will, in turn, inform decisions on how many banknotes we need to print to ensure that demand is met.

Critically, it is clear that cash remains important to many in society. The Bank, and UK authorities, are committed to cash, and together we are taking action to ensure that the wholesale cash distribution infrastructure remains effective, sustainable and resilient in a lower cash usage world. The new legislation, which will protect cash by ensuring its continued access and provide the Bank with powers over wholesale cash distribution, is a significant step to helping us achieve this.

We will continue to work closely with the cash industry and other authorities who have responsibility for cash to ensure that cash remains available and accessible for those who want to use it.